All Saints’, Dorval

September 21, 2025

This was a tough one. I preached it twice, at 8 and 10 am, and it wasn’t quite the same sermon on each occasion. If you perceive gaps or have questions, leave a comment – it would certainly make a nice change from deleting endless identical spam comments on this blog!

This is one of those Gospel passages that sends the preacher scurrying for her commentaries. Or, alternatively, for her script of The Man Born to be King, in which Jesus tells this story with the punchline, “Fellow, you’re a thorough scoundrel – but I do admire your thoroughness!” (And Matthew, the former tax collector, is the one who laughs the loudest).

As is so often the case, understanding this parable depends on understanding how things worked in the hinterlands of the Roman Empire in the first century – a time and place which, more’s the pity, our own time and place are increasingly coming to resemble.

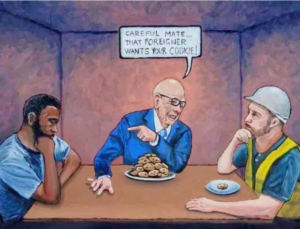

In Palestine in the time of Jesus, there was vast inequality of wealth; most people were heavily in debt and had a hard time affording property; and the few who did have large fortunes had amassed those fortunes largely by extracting punishing sums of interest from everyone else. The manager in this parable is one of the people on the ground, doing the extracting.

Meanwhile, the Jewish law very clearly forbade the charging of interest, on the grounds that it hurt one’s neighbour and unnaturally caused money to “breed” as though it were a living thing, like a cow or a fig tree.

It’s very possible that in sitting down and writing off the profits with the master’s debtors – essentially revealing to them how badly the original contract had snookered them – the manager is becoming a class traitor: the high-flying Wall Street intern who suddenly turns around and hands over several fat bank accounts to the student organization protesting down the street, or to the undocumented wage workers standing around on the corner waiting to be offered a job. (Maybe the manager had already been doing that, hence the charge of “squandering his property” that led to the master firing him.)

Instead of breeding for an already unimaginably wealthy patron, the money is now being put to actual use for a human being who needs it to feed and clothe themselves. And by giving up his cut, now that he’s lost his job, the “dishonest” manager is making sure that he will be taken care of once he rejoins that world of people who have bills to pay and kids to feed – and at least he won’t have to dig or beg.

Jesus explicitly tells his listeners to use possessions to achieve their goals in God’s kingdom. To quote a fellow pastor with whom I was chatting about this story online as we both worked on our sermons (several lectionary cycles ago): “The dishonest manager used his wealth to secure the future he wanted for himself; how do we use our wealth to secure the world we want?” What are we building, and why, and how does it fit into God’s dream for the world?

Jesus hammers home his point at the end of the story, with those repeated phrases: “Whoever is faithful in a very little is faithful also in much; and whoever is dishonest in a very little is dishonest also in much. If then you have not been faithful with the dishonest wealth, who will entrust to you the true riches? And if you have not been faithful with what belongs to another, who will give you what is your own?”

Here, the “little” means the use of money, and the “much” means the response to God. We’re not talking about a little money versus a lot of money, or even ill-gotten gains versus honestly earned wealth. We’re talking about what’s inessential versus what’s essential; in the words of a beloved collect, the “things that are passing away” versus the “things that shall endure.” This is underscored by the fact that when Jesus refers to “what belongs to another,” he means possessions – even those that theoretically belong to us – whereas when he refers to “what is your own” he means one’s own soul and its relationship with its Creator.

In several places, especially toward the end of the passage, the word translated “wealth” in Greek is “mammon”. There is some wordplay here, because the best guess at the etymology of “mammon” is that it means “something to rely on,” and of course, Jesus’ entire point is that mammon is not to be relied on, unless one uses it for God’s purposes.

(This is one of the few Scriptural passages that I often quote in the King James Version, because let’s face it, compared to “make friends for yourselves by means of dishonest wealth”, “make ye unto yourselves friends of the mammon of unrighteousness” just sounds so much cooler.)

Mammon, in fact, is an idol: something that we are tempted to worship, something that we are prone to put in the place of God, but that is not worthy of worship – something that, in fact, if we worship it, we are rejecting God – something that is only useful if it is devoted to God’s purposes. Indeed, we cannot serve two masters.

What we do with our money expresses our priorities: this is not a new or surprising thing to say.

What I think we struggle with, in this passage, is how difficult it is to distinguish between faithfulness and dishonesty. That’s what makes us uncomfortable. We want clear lines, areas of black and white. We want it to be easy to tell when we’re doing wrong and when we’re doing right.

But even if you assume that part of what this story is doing is revealing the brutal inequality of life in first-century Palestine – or, more accurately, highlighting it, because everyone listening to the story would have been well aware of how hard it was to survive in that context! – it still resists easy categorization, and it’s hard to know for sure who are the good guys and bad guys.

I confess, as we contemplate scaling some very challenging financial hills in the coming months and years, that this story makes me mad in some of the ways I suspect it made Jesus’ listeners mad. It makes me mad that a handful of people who seem to have lost all touch with the needs and hopes of normal people control the vast majority of the world’s wealth. It makes me mad that trillions of dollars can slosh around the global financial system for things like AI and fossil fuel subsidies while a little church in suburban Montreal has to beg and scrape for the money to rebuild our endowment after we fix our roof, so we can keep on being a community of love, hope and faith. I would like some unrighteous mammon to fall into my lap, thank you very much.

I think that perhaps the most essential message of this parable is that by its very complexity – by the difficulty of unraveling what it is that Jesus means by telling us to “make friends for yourself by means of dishonest wealth” – it breaks down the division that we want to make between our possessions and our spiritual lives.

It makes the point that it’s not about putting the “profane” stuff, the dishonest wealth, the hurly-burly of the business world, the mundane details of property and possessions, in one box over here; and putting the “sacred” stuff, the elevated emotions, the prayers and scripture and hope of heaven, in another box over there; and keeping the two rigorously separated.

That’s not only impossible, it’s undesirable. The world is irrevocably mixed, jumbled and juxtaposed. The sacred and the profane, the spiritual and the material, can’t be separated. And they shouldn’t be. Our hope of heaven is inextricably tied up with how we respond to God here, in this life.

After all, we worship a God who became flesh and who hung out with people who had gotten rich by exploiting their neighbors (something I find increasingly hard to stomach, honestly, the more outrageous the behaviour of the global elites becomes). We worship a God who uses the tremendously imperfect, crazy tapestry of our human lives to accomplish God’s good purposes; a God who is crafty, sneaky, savvy, in the way he works with the materials available to him, and who encourages us to do the same, for the purpose of building up God’s kingdom.

It may not be neat and tidy. It may disrupt our comfortable, rule-following certainties and reveal the ways in which the system is rotten to the core. But apparently that’s the way God likes it – and on the other side of the scary jump into the unknown, there is a community that takes care of each other.

Amen.

Leave a Reply